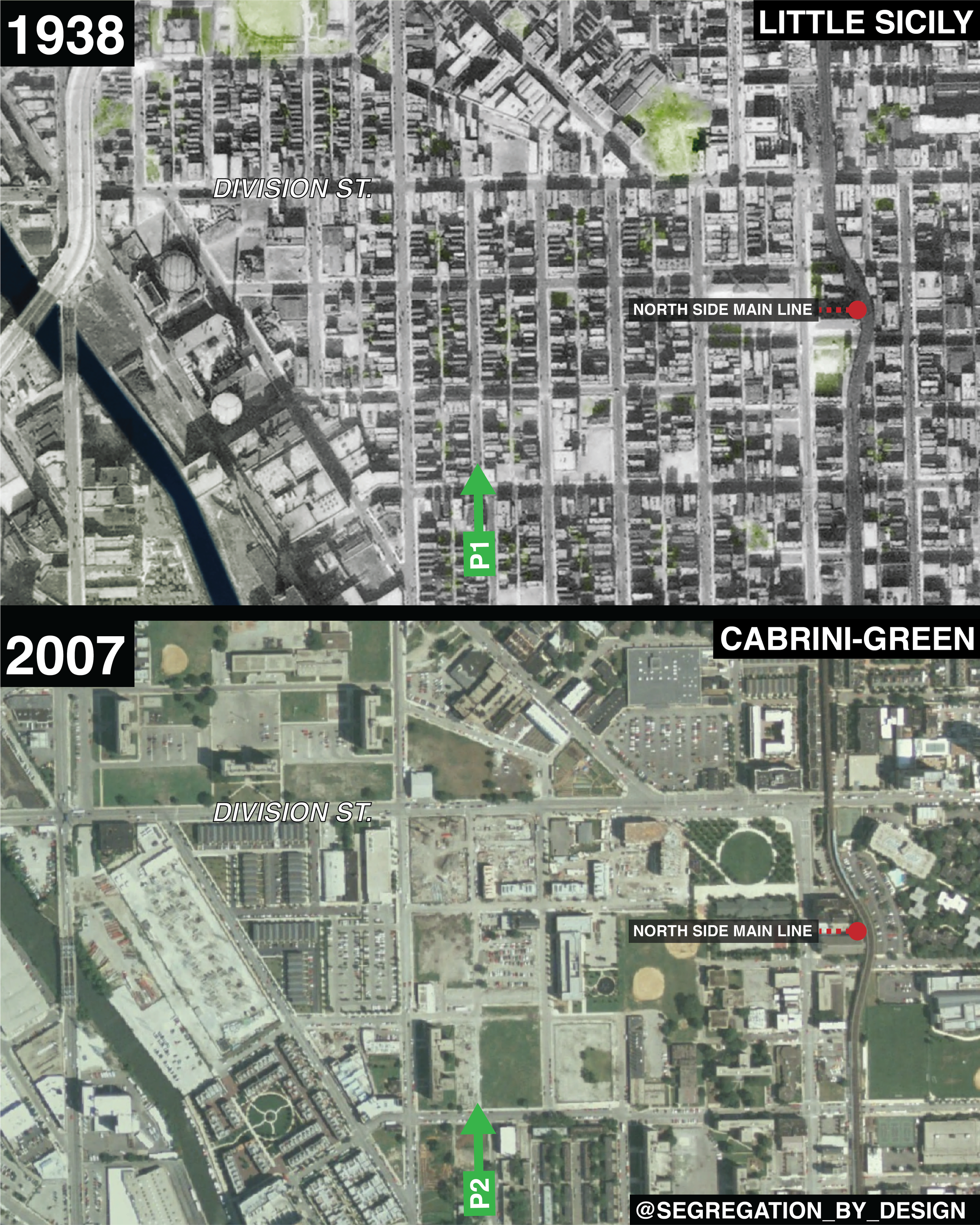

CHICAGO: NEAR NORTH SIDE

The Near North Side of Chicago, before and after government-funded “urban renewal.” Much of this Italian and Black neighborhood was leveled in the 1940s for the construction of the Cabrini-Green public housing project, which due to lack of maintenance and design flaws was itself demolished in 2011 (but is still visible in google streetview after toggling to 2007, as seen in this image). The site today is vacant, but market-rate condos are being built, continuing the recent trend of gentrification in the area.

Prior to the construction of Cabrini-Green, the neighborhood was known as Little Sicily. Home to many Italian immigrants, by the 1940s the neighborhood’s population was also roughly a quarter Black. Because of this Black and immigrant population, the govt redlining map of Chicago officially states that the neighborhood “has no future.”

The redlining comments for the neighborhood go on to say: “Negro population is largely concentrated south of Division St., but a continued infiltration of this race has caused an overflow north of that point; it is reasonable to assume that the section may eventually become more negro than Italian, which is the other predominating population class residing in this section” (Source: @urichmond).

Because the neighborhood was located adjacent to one of Chicago’s wealthiest areas, the famed “Gold Coast,” officials wanted to minimize “overflow.” To do so, beginning in the 40s the city began razing Little Sicily and replacing the formerly dense neighborhood with shoddily-built, segregated housing projects: the Cabrini-Green Homes.

The goal of these projects was containment through segregation: the neighborhood, which had been a diverse mix of people occupying the same buildings, by the 60s had become a series of isolated, racially-divided silos. Any people of color moving into the neighborhood had no other options than the new projects—everything else was either whites-only, or it had been leveled. The same was true in much of the rest of the city.

(So egregious was the discrimination in Chicago’s public housing system, that in 1966 the Supreme Court found the Chicago Housing Authority (CHA) liable for violation of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.)

Between the 1940s and 1960s as the Cabrini-Green projects were growing, quarantining more of the neighborhood, so too were the city’s finances simultaneously faltering. Newer projects were built increasingly cheaply, and basic services like routine building maintenance, trash collection, and pest control were eliminated. Lawns were paved over to reduce maintenance costs, and units which fell into disrepair were simply boarded up.

Over time as the complex deteriorated, Cabrini-Green gained a hyperbolic reputation for crime which was sensationalized in the media. Ignoring the history of legal neglect and disinvestment, much of the media and public simply blamed the residents, speaking in language replete with dog whistles and euphemisms to explain the failure of public housing.

Despite the organization of tenants led by activists such as Marion Stamps who were demanding improvements to public housing, instead of reinvesting the city began demolishing the complex in 1994 and selling the land to private developers (who were enticed by the neighborhood’s proximity to the Loop). Twice within 50 years the Black community of the Near Northside has faced destruction.

While the city promised to rehouse tenants in new, privately-developed affordable housing, by 2001 the demolition had far outpaced new construction, leaving some of the 15,000 former tenants to simply become homeless (source @chicagosuntimes, 2014). As of today, some new affordable housing has been built, but market-rate housing now completely surrounds the site as the forces of gentrification overtake the area.