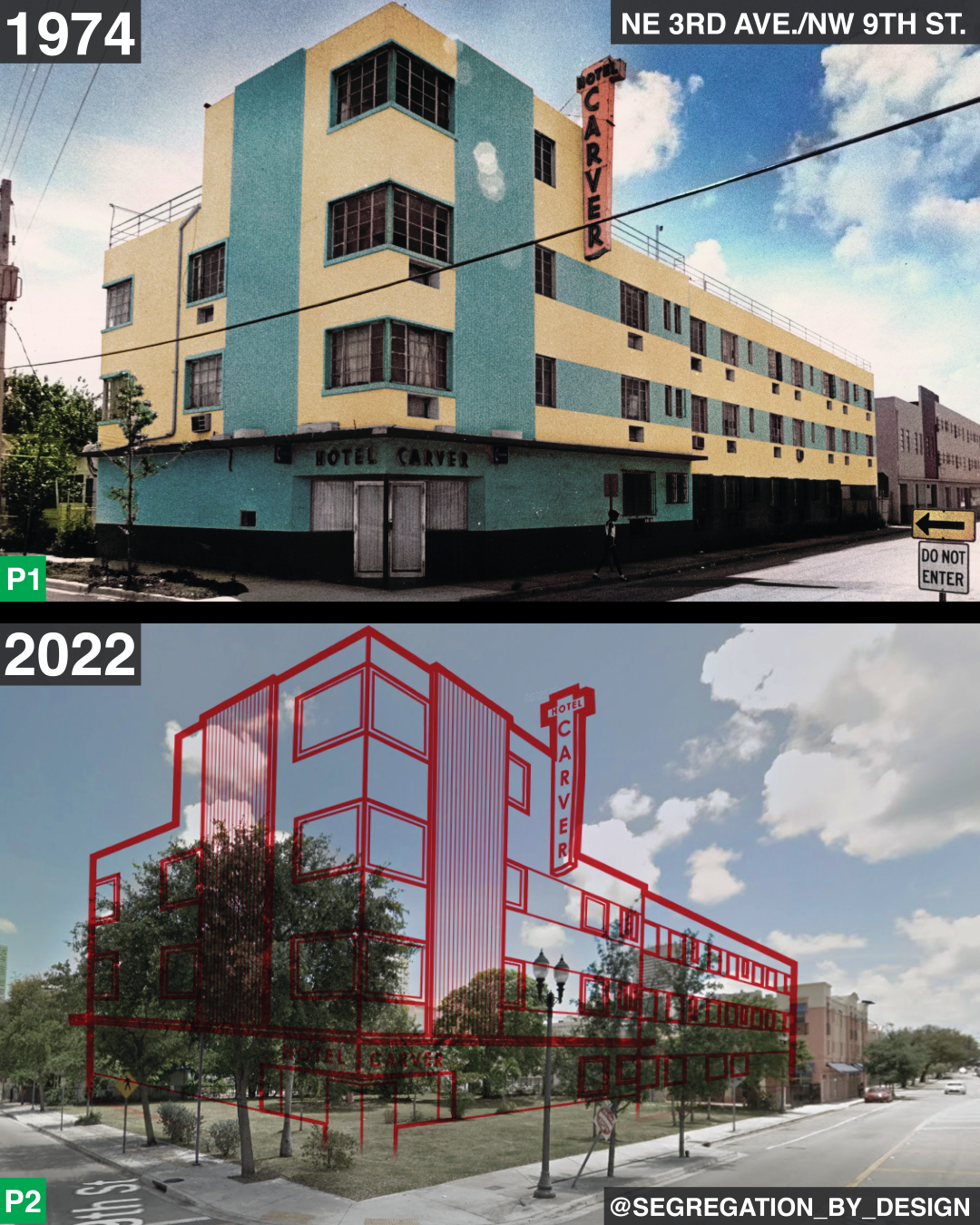

OVERTOWN: CARVER HOTEL

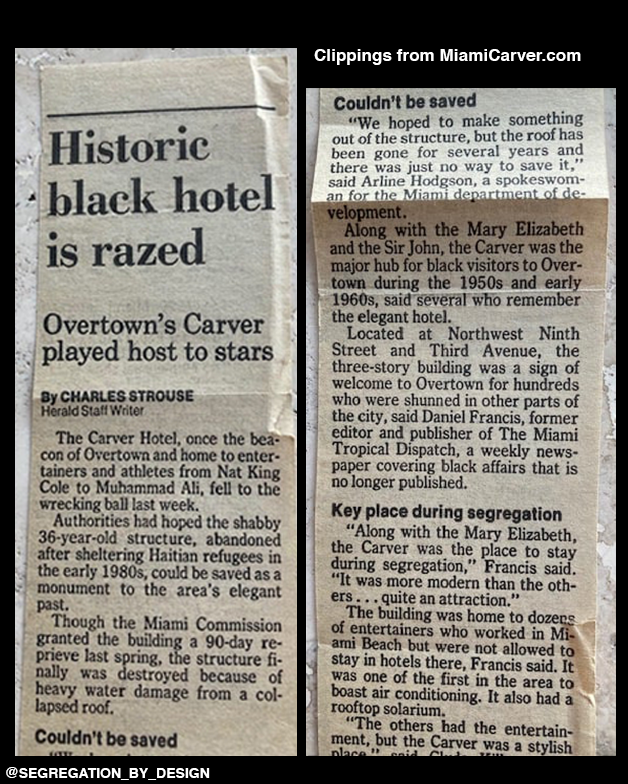

“The Carver was the place to stay in Overtown, along with the Mary Elizabeth and the Sir John [later renamed Lord Calvert]” writes the Miami Herald in 1990. “The Carver was a major hub for black visitors to Overtown during the 1950s and early 1960s, said several who remember the elegant hotel. Located at NW 9th St. and 3rd Ave, the three-story building was a sign of welcome to Overtown for hundreds who were shunned in other parts of the city [due to the color of their skin]. The building was home to dozens of entertainers who worked in Miami Beach but were not allowed to stay in hotels there” due to official segregation. See the complete Herald article in the 3rd and 4th images.

In 1990, the Carver was demolished. When I-95 cut through Overtown in the 1960s and destroyed many of the neighborhood’s historic businesses and entertainment venues, patronage at the hotel dropped until it finally went out of business in the late 70s. The building was abandoned and eventually torn down.

In all, construction of I-95 in Miami required the forcible relocation of over 12,000 residents in Overtown—nearly 100% of them black. In the 1960s the government used eminent domain to seize buildings across the heart of Miami’s black community in Overtown in order to build the highway. Authorities compensated building owners with amounts well below market rate, and offered renters—the vast majority of the community—nothing at all.

The highway drastically widened Miami’s existing “color line,” which had originally been established by Henry Flagler’s FEC railroad tracks, separating white Downtown from black Overtown. Before the 1960s, official Jim Crow segregation laws severely limited housing options for black Miamians, with Overtown being the only central location not officially “whites only.” Despite resulting overcrowding and profiteering from white and black landlords alike, the neighborhood maintained a strong black middle class with hundreds of locally-owned businesses lining 2nd and 3rd Aves.

After the highway decimated the neighborhood, the population dropped from roughly 50,000 to around 10,000. As N.D.B. Connolly notes in his history of Miami, A World More Concrete, “The resulting disruption and pain many of these [highway, urban renewal, and slum clearance] projects wrought was not, as some have argued, the result of some political accident or bureaucratic misstep on the part of otherwise earnest housing reformers. Displacements were intentional. They represented, for growth-minded elites, successful attempts to contain black people and to subsidize regional economies with millions in federal spending.”