MIAMI: OVERTOWN

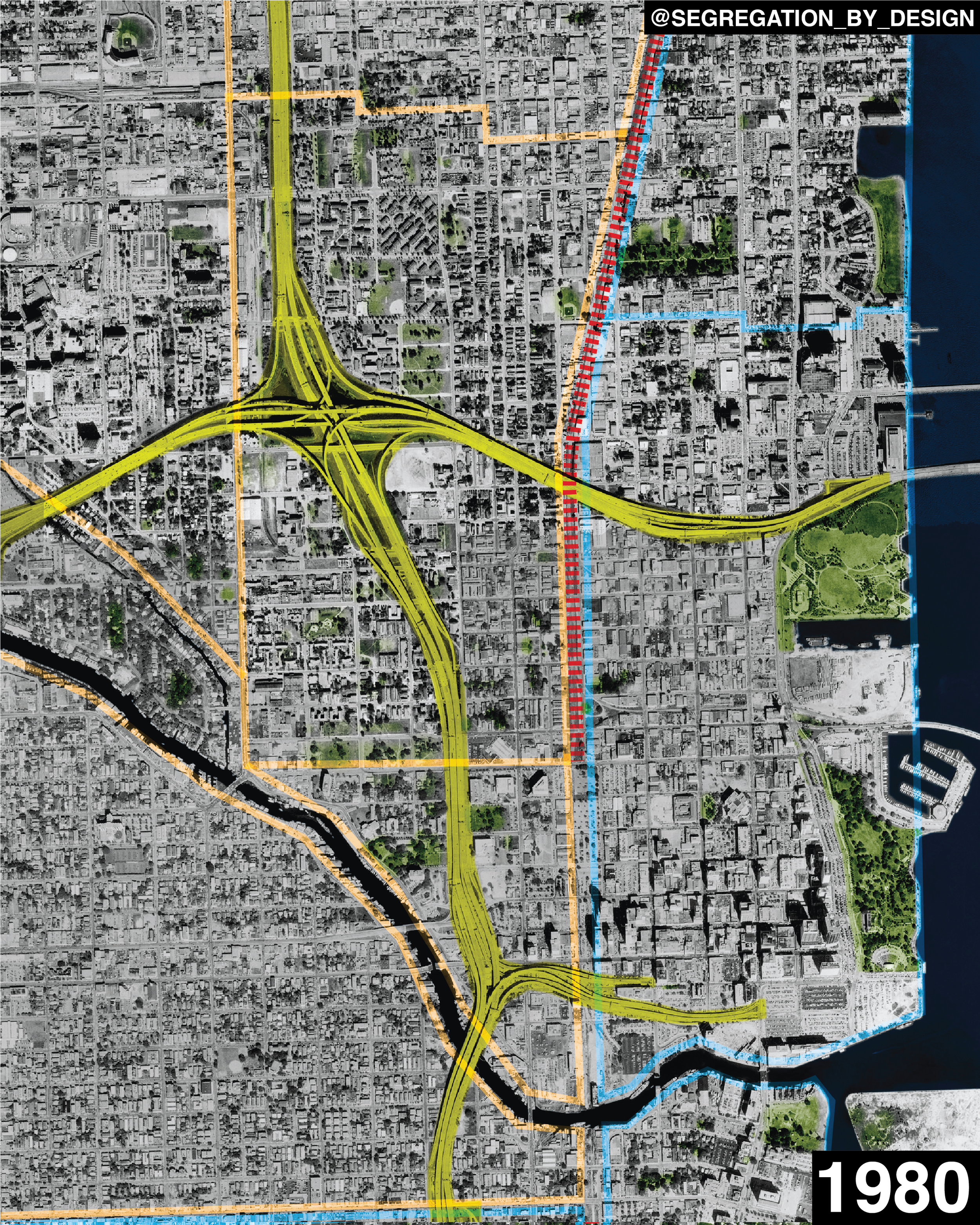

Downtown Miami and Overtown before and after highway construction and “urban renewal.” In all, construction of I-95 in Miami required the forcible relocation of over 12,000 residents in Overtown—nearly 100% of them black. In the 1960s, the federal, state, and city government used eminent domain to seize buildings across the heart of Miami’s black community in Overtown in order to build the highway and related “urban renewal” projects, which dropped government and institutional buildings (and parking—lots of parking) on top of the formerly residential and commercial core of the neighborhood. Authorities compensated building owners with amounts well below market rate, and offered renters—the vast majority of the community—nothing at all.

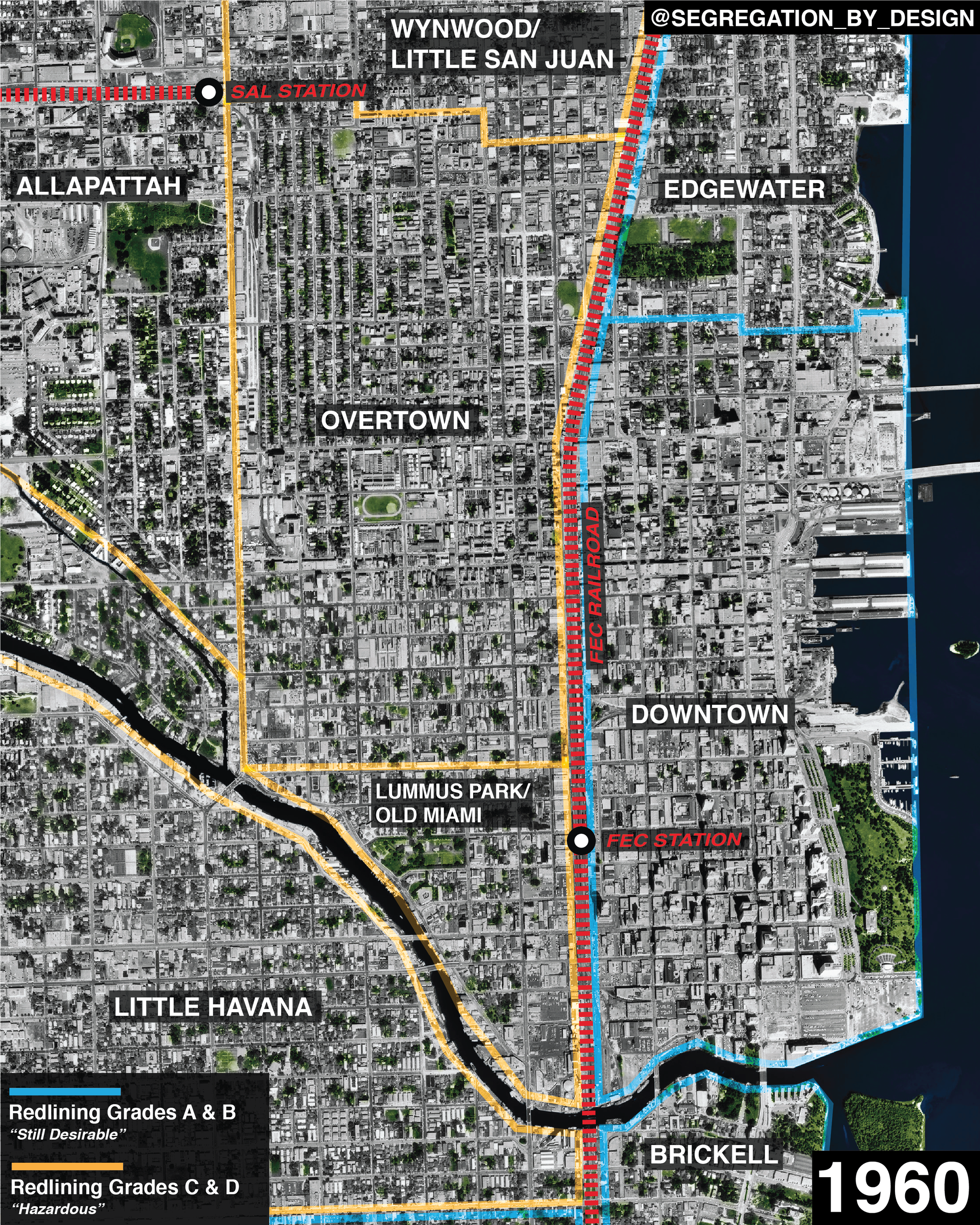

The highway drastically widened Miami’s existing “color line,” which had originally been established by Henry Flagler’s FEC railroad, separating white Downtown from black Overtown. Before the 1960s, official Jim Crow segregation laws severely limited housing options for black Miamians, with Overtown being the only central location not officially “whites only.” Despite resulting overcrowding and profiteering from white and black landlords alike, the neighborhood maintained a strong black middle class with hundreds of locally-owned businesses lining 2nd and 3rd Aves.

After the highway decimated the neighborhood, the population dropped from roughly 50,000 to around 10,000. As N.D.B. Connolly notes in his history of Miami, A World More Concrete, “The resulting disruption and pain many of these [highway, urban renewal, and slum clearance] projects wrought was not, as some have argued, the result of some political accident or bureaucratic misstep on the part of otherwise earnest housing reformers. Displacements were intentional. They represented, for growth-minded elites, successful attempts to contain black people and to subsidize regional economies with millions in federal spending.”

Similar to the way the federal government enabled the destruction of roughly 1,600 Black neighborhoods between 1940 and 1970, municipal and state planners (using federal funds from the 1949 Housing Act and the 1956 Federal-Aid Highway Act) deemed Overtown to be a “blighted slum.” As was typical of government planning at the time, the vibrant urban reality of Overtown was either ignored or held in contempt.

Overtown was no slum. Founded in 1896 during the era of official government segregation, Overtown was one of the few desirable places Black Miamians were permitted to live until the 1960s, populated with large communities of Caribbean, Latin American, and South American immigrants, as well as migrants from across the American South. The neighborhood became known as the “Harlem of the South,” owing to its booming economy and entertainment scene. Overtown was centered on Second Avenue, known as Little Broadway, and its streets were lined with hundreds of Black-owned businesses, including “dentists, law offices, restaurants of every flavor, laundries, beauty salons, and drugstores,” Connolly wrote. Between businesses were “wide, large brick and stucco homes, some with two stories, large front porches, and, occasionally, two and three bathrooms to spare. These belonged to Black Miami’s professional class.”

By the 1950s, Overtown was the center of nightlife on the mainland for Miami’s Black, Latino, and white populations alike. Similar to the popular South Beach neighborhood on the barrier island opposite Biscayne Bay in the “whites only” city of Miami Beach (where nonwhite people were required to obtain visitors’ “passes,” which came with a 6 p.m. curfew), Overtown in the 1940s and ’50s was a riot of art deco and streamline moderne, awash in neon and vibrant marquees of all colors (see previous post for one such example: the art deco Hotel Carver).

World-renowned musicians and entertainers such as Count Basie, Ella Fitzgerald, Cab Calloway, Josephine Baker, Billie Holiday, and Nat King Cole would often perform in Overtown’s clubs and theaters yet were barred from staying in Miami Beach because of the color of their skin. Venues such as the Knight Beat Club at the Lord Calvert Hotel, the Harlem Square Club, and the Lyric Theater ensured that Second Avenue lived up to the Little Broadway nickname. With its many hotels featured prominently in the Green Book, a travel guide that listed businesses that would accept Black customers, Overtown became a vacation destination for Black Americans from around the country.

Moreover, Connolly explains, “One paradox of colored [sic] housing in the postwar United States was that, while often in bad physical shape, black homes were usually on what city planners and commercial real estate developers were increasingly imagining to be some of the most valuable land in American cities. The county’s old colored towns—vividly rendered in dance, as was Detroit’s “Black Bottom,” or at time entirely fictionalized, as in Ann Petry’s “The Narrows”—served, for years, as very real “servants quarters” for Negroes [sic] servicing white privilege prior to and immediately following WWII. In the expanding cities of the 1940s and 50s, neighborhoods bursting with black workers seemed less like an asset than a hindrance. They ran up against blossoming downtown business districts featuring “whites only” hotels, department stores, and universities. As a second paradox, unique to the urban south, the residents of Dixie’s colored enclaves were, by the sweat of their brows, supposed to man the material emergence of the modern New South city. They also represented, through their very bodies, the kinds of colored servility most whites deemed a southern tradition or, in Greater Miami’s case, an added perk of Carribean vacationing. A central tension of the postwar period, thus, was that colored neighborhoods were both racially necessary and, increasingly for many, economically expendable.”

In this vein, “Planners viewed Overtown as having some of the most valuable land in FL, laying less than 1mi west of the center city”—a perfect opportunity for “urban renewal.”

“As a general feature of urban renewal, demolition tended to come swiftly [in neighborhoods designated “slums,” such as Overtown”], but the building of affordable housing units, because of landlord resistance, took much longer. Around the United States, roughly four hundred thousand residential units were demolished under urban renewal by 1 July 1967. Landlords ensured that fewer than eleven thousand low-rent public housing units were built on those sites. In Miami, demolition began in the Central Negro District [the city’s official designation for Overtown] in 1965, first for the highway and then through a series of urban renewal zones. But construction of new housing in the urban renewal areas did not begin until 1969, which was when landlords who had existing interests in the community finally secured the desired terms on new building contracts.”

Connolly continues, “[Urban Renewal] highlighted the fact that, for black and white property owners, all landlording was not equal. Indeed, once actual demolition began, the lived experience of land expropriation offered a study in racial contrasts. ‘When we really understood what was happening,’ remembered Marian Shannon, a black homeowner in the Central Negro District, ‘people...almost gave their homes away because there was nobody to advise them on how to deal with these people who were buying it up.’ Rachel Williams recounted, ‘They sent us a notice and a check for $7,000 for two double lots...and most of us got these checks from the city and we thought we just had to move.” Learning later that she had sold her house and adjoining family residence at a significant loss, Williams lamented, ‘At the time we were not educated to the point to know that we didn’t have to take that.” (Connolly, 261-262)